A lion in winter vs. the rabbit chaser: As Tom Izzo reinforces his greatness at 70, new rival Dusty May hunts

Michigan State is again king of the Big Ten. Can Dusty May one day do for Michigan what Tom Izzo has for MSU? An under-appreciated rivalry gets a compelling reboot

Michigan State has employed one coach for 30 years. Dusty May, meanwhile, is Michigan's sixth in the past three decades.

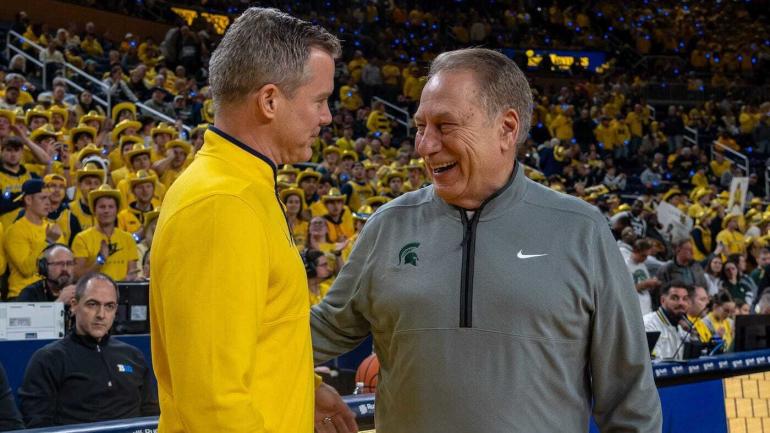

As Tom Izzo continues to thrive in the winter of his Hall of Fame career, his younger counterpart in Ann Arbor is at the beginning of what could be a fruitful long-term tenure. The juxtaposition between two coaches separated by 22 years and more than 580 wins creates a compelling new narrative in an under-appreciated basketball rivalry. The two will meet Sunday at noon ET on CBS.

Matt Norlander spent time with Izzo and May in late February to get a sense of how two very different men are running programs at drastically different points in their careers.

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Hunched over, head bobbing at a quarter-note rhythm, jaw slightly dropped, eyes in constant scan. His hands clenched, tugging on the knees of his polyester pants. A whistle dangles around his neck.

Tom Izzo is exactly where he wants to be at 70 years old: overseeing yet another Michigan State practice.

Eventually, there's an inevitable mistake from one of his players. Izzo doesn't even think to use his whistle; he reflexively barks, and in a beat, the Hall-of-Famer is hoofing downcourt. It's two days before MSU's big road game against first-place Michigan and Izzo isn't satisfied by the lack of physicality in the painted area.

One of his guys backed off under the boards during a drill. I'm sitting too far away to hear Izzo's initial verbiage as he approaches the perpetrator, but after some quick one-sided discourse Izzo's final six words are enunciated loud and clear and they reverberate across the practice gym.

"KNOCK SOMEBODY ON THEIR F---ING ASS!!!"

If the point wasn't direct enough, about 25 minutes later Izzo scolds the same six words again to another player, only more drawn out and a little louder this time, to make sure the message is effectively punctuated — and no longer ignored.

These are portraits of Izzo as you likely imagine him, but it's also important to note that there are many encouraging moments over the course of a two-hour Michigan State practice. He smiles plenty, he loves on his guys. But, yeah, he's an absolute red ass. These are the times and spaces wherein Izzo's players are hardened and sharpened. At one point he gets on one of his guards with comical exasperation: "One good game? One good game and now you're going to take a week off? One good game?!"

For Izzo, coaching has meant "living my dream." It took three years for a young Izzo to convince Jud Heathcote to hire him as a low-level grunt guy on a $4,800 salary. He arrived in East Lansing with a broken jaw (softball injury) in 1983 and never left. Few have been able to do what Izzo has done in this regard: He walks the line of being so consistently, publicly fiery about the performance of his players while being lauded by some for the big-hearted intentions that embolden his oft-incandescent behavior.

For all that comes with being the coach of one of the biggest programs in the sport — and how that job has changed, drastically, as Izzo's gotten older — the guy from Iron Mountain, Michigan, has kept his motivations simple.

It's about winning.

That bore you? Too bad. Sounds cliche? There's the door. Doesn't inspire you? Then you're nobody Izzo wants to spend time with, let alone coach or work alongside.

"There's a lot of ways to win games. I don't think there's a lot of ways to win championships," Izzo told CBS Sports. "It's hard for winning to be number one for a lot of players. And what winning usually brings is all those other things they want."

The outcome of every game, every practice drill, every day on the job, every facet to why he still devotes the majority of his life to the vocation comes back to the fundamental charge of beating the other guy. While it is not the only reason he is still doing this into his eighth decade on Earth, it is far and away the biggest. Few coaches have soldered their identity of What It Takes To Win, down to the mitochondrial level, like Izzo.

"Over the last five years, (the) whole world has changed — unaccountability and everything — I've had to adjust to that," Izzo said. "People perceive me as a guy that's getting on somebody, and I never understood that, I really didn't. I mean my own kids, they don't do what they're supposed to do, my job's to hold them accountable. I don't look at players any different."

This approach to coaching, whatever you want to call it, just don't use "old school." Izzo hates that.

"It irritates me, because old school means you don't want to adjust or change," he said. "I want to adjust and change. I just don't want to lose the principles of what I know it takes to be great."

Get Izzo going on those principles and he's in fifth gear in seconds. His decades-long friendship with Nick Saban is well known at this point. Even more than a year after Saban retired, Izzo still leans on those philosophies that turned Saban into a mythical-type figure in the annals of American sports coaches.

"I heard everybody say, he's never happy. I heard everybody say, he's hard to play for. Heard everybody say he's hard to work for. Yeah, you idiots. That's because he's trying to do something that only one half of 1% of the world can do," Izzo said. "The biggest thing that I hear now that bothers me — and I'll never change it, I'll never not let it bother me — is winning AS important, or are all these other things more important than winning? And when I figure out that they are?"

Izzo takes his right hand, lifts it to his forehead and salutes.

"Sayonara."

In the past couple of years there had been murmurs in college basketball that maybe retirement was coming for Izzo the way it caught coaches older and younger than he: Roy Williams, Jim Boeheim, Mike Krzyzewski, Jay Wright and Tony Bennett. He reiterated in a two-hour sit-down with CBS Sports that retirement isn't around the corner.

"The truth of the matter is, I think I'm healthier than I was five years ago," Izzo said. "They say that you'll know when it's time. It doesn't feel like it's time, not for me."

Izzo semi-regularly receives calls from a few guys — some active, some retired — who tell him he can't quit. The game needs him.

"I don't think anybody understands what it's like, day to day, to think somebody's calling your kid, and all of a sudden he turns into an asshole in practice, and for just no reason," Izzo said. "I've said these kids can't play at this level half pregnant. You're either in or you're out, man. Not even if you want to win a championship, but if you want to just ... exist and win games."

Michigan State has had a lot of turnover as a university, and yet Izzo's still there. He is the embodiment of, and really the spokesperson for, that place more than probably anyone ever. He's outlasted multiple iterations of athletic directors, presidents, vice presidents, football coaches, you name it. He remains invested because, over the past year or so, he's come to terms with letting go on some issues in college sports that he'd like to see fixed, but doesn't believe will be by the end of the decade.

"I've found a way to say I'm going to try to adjust," he said. "I'm going to try to do the best job I can for my players, but I'm not going to fixate over it every day. ... I'm passionate about it. I'm not obsessed with it anymore. I know I can't change it."

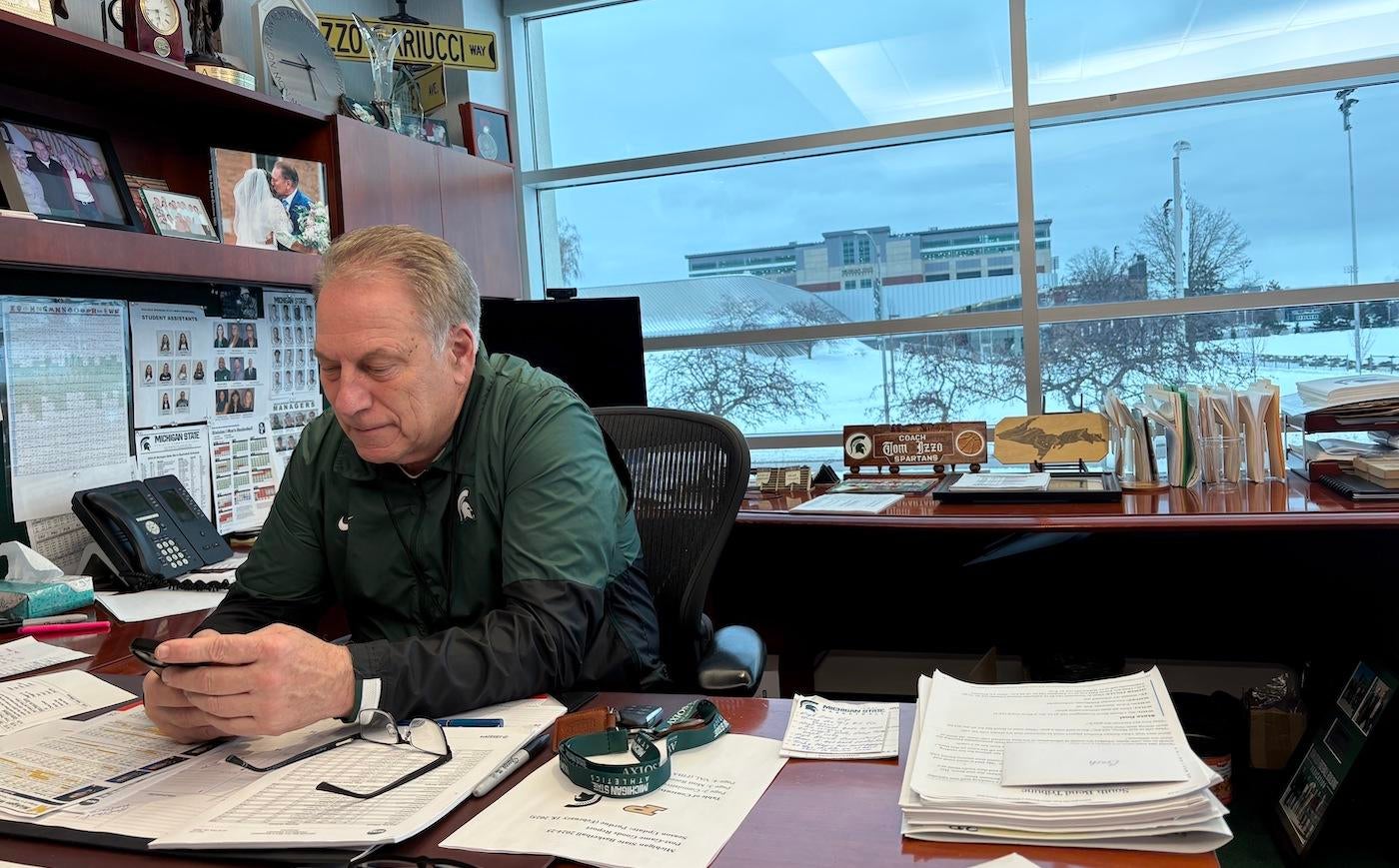

What he does fixate on are the practice plans, the game tape he watches in the office — then at his house every night, often well past midnight. When his players are enjoying college life away from the facility, Izzo is thinking about how he can make them better.

MSU (25-5) is really good yet again. Maybe even great. This doesn't just magically occur because a well-known coach who's made every single NCAA Tournament since 1998 happens to be walking the halls. It's thousands of hours every year devoted to working, wanting, willing winning seasons into existence.

Four months ago, MSU received the seventh-most votes among Big Ten teams in the preseason AP poll; the Spartans were unranked. Over the past three months they have wormed their way up in the rankings. This week they sit at No. 8, and on Thursday night clinched the standalone regular season Big Ten championship with a 91-84 road win at Iowa. It's Izzo's 11th regular-season Big Ten crown, tying him with Bob Knight and Ward "Piggy" Lambert for most in Big Ten history.

The Spartans didn't even give Michigan hope for a share of the title when the teams meet Sunday. Izzo cannot stand losing to Michigan, and for most of his career he's avoided the feeling, owning a 35-16 record against the Wolverines.

Remarkably, this year marks the 22nd time in 30 seasons that Izzo's Spartans will finish above the Wolverines in the Big Ten.

It's astounding what this team has done over the last month, staring down the toughest schedule in the Big Ten and refusing to blink. MSU responded to an unexpected home loss to Indiana on Feb. 11 with five straight wins, all of them against top 25-level teams: Illinois (road), Purdue, Michigan (road), Maryland (road), Wisconsin. Iowa isn't in that class, but it was another road game and it went MSU's way in tidal wave fashion after the Spartans hung 61 second half points on the Hawkeyes.

What awaits at the Breslin Center on Sunday? The stakes may be lowered, but you'd be a fool to think Dusty May isn't champing at the bit to exact revenge and send MSU into the Big Ten Tournament with a loss, solidifying Michigan as the clear-cut No. 2 team in the league in the process.

Meanwhile, in Ann Arbor

Until the back end of February, it looked like May was going to make Michigan kings of the Big Ten immediately. The Wolverines led the conference for nearly a month until their 75-62 home loss on Feb. 21 to MSU. Since then, U-M has gone 2-3 and, by virtue of MSU's win Thursday, is playing for second.

Still, the program's first-year gains under May could be an indication of a new era of sustained success. The Wolverines won only eight games last season in the disastrous end under Juwan Howard. At 22-8, this is the biggest single-season turnaround in school history. An instant program flip will catch a lot of people's attention. With the Indiana job set to open later this month, May was previously a potential target at his alma mater. Instead, he agreed to a contract extension on Feb. 21, when he told CBS Sports, "I'm staying at Michigan."

With May's future secured in Ann Arbor, he could make for an interesting challenger for Izzo in the years to come, primarily because he's unlike any previous Michigan coach who's battled Izzo. Steve Fisher, Brian Ellerbe, Tommy Amaker, John Beilein, Juwan Howard all caught Izzo at different points along his Hall of Fame journey. They were all coaches of different styles and different levels of success prior to getting the Michigan job.

They all left with a losing record against Izzo.

None of them did what May has a chance to do Sunday: win his first game at MSU. The last Michigan coach to do that was Johnny Orr in 1969.

May arrived with a Final Four on his résumé and the aptitude to deftly handle the job. He took a severely under-financed FAU program to the biggest stage in the sport, but beyond that, he never had a losing season and wound up winning 65% of his games at a place where most coaches would have struggled to tread water.

While Izzo is often a red-faced competitor on the sidelines — seemingly living and dying on every other possession — May's demeanor is just the opposite. His even-keeled temperament calls to mind the disposition of a 10-year NBA coach. That's reinforced by a problematic personality trait for the college game: May doesn't like to chide officials. In fact, he rarely goes after them. It's so noticeable in the coaching ranks that some have approached May over the past three months to tell him that if he didn't up the antagonizing, his teams were going to get burned.

"I've gotten so much unsolicited advice," May told CBS Sports. "Hey, you're probably going to have to get on this guy a little bit or he's going to give them the calls. It's not what I want to be doing. I don't want to be complaining about calls as I'm trying to coach basketball."

May's unflustered sideline demeanor belies the one quality he shares with Izzo: obsessive competitiveness.

"I've never seen a head coach watch as much basketball as Dusty May," Wolverines assistant Mike Boynton said. "I'm talking college games, high school games, Euro games, NBA, old footage, whatever. He talks to basketball coaches probably for 16 hours of his day about different ideas. He's obsessed with it, particularly offensively."

Obsessed. Enjoyment. Growth mindset. Joyful. Emotional intelligence. These are the words those who know May best use to describe his approach to the job. He hates long meetings and looks for his staff to feel emboldened, to bring their ideas to him daily, to be efficient in service of others.

"There's 10 people in a room," says May, "you stay in there for an hour, that's 10 man hours."

Sometimes meetings are necessary. Often times, coaches have meetings just to feel like you need to have a meeting. For May, that's not how you make a program better in the day-to-day.

"Just sitting in a room, wasting time," he says.

These qualities are what made him the most coveted coaching candidate in the spring of 2023 and 2024, before he ultimately chose Michigan over Louisville and Vanderbilt.

"Dusty has the best temperament of anyone I've worked with," Boynton, who coached Oklahoma State for seven years, said. Boynton knows what it means to have the big office, to be the last out of the tunnel before tip, to carry all of those expectations and live with the pressure that comes with a high-major job. "Literally, if you walked into the office after the Purdue game or after the UCLA game you would not know which game was which. He's the same every day. He's very open. His balance of confidence and humility is unmatched."

To get a sense of the contrast: May graduated high school the same year Izzo began his tenure at Michigan State. In the late '90s, Izzo's teams beat Bob Knight's Hoosiers more often than they lost. Izzo and May were in the same building more than a half-dozen times together, as May was a do-it-all pleaser picking up towels and chasing after rebounds in pre-game warmups as a team manager.

"I felt like that was my path to get into coaching," he said. "And so whatever it was was worth it, because I had no other way to set myself apart from anyone else."

Ever since May was in middle school, he felt a calling to coaching. The smells and sounds of a basketball gym have lured him, constantly. He feels now, at 48, what he felt at 12 when walking into a building made for basketball.

"That was our barbershop, that was our cafeteria, that was the hang out, in the gym," May said. "You're just in the gym. Shooting, playing, hanging out, watching the young guys play, watching the old guys play. Just our background: you're just in the gym. I love being in the gym. Ball bouncing, shoes squeaking, the talking, the chatter, the nets. That's probably the most enjoyable part of the job, because at the end of the day, that's still what the game is. It's what drew all of us to this. I know we like to say we do this to take care of our families. There's a million things you can do to take care of your family. Selfishly, I get to be on a team. Fifty-year-old men still get a chance to still be on a team and be in the gym and wear sweats every day. It's pretty cool job."

Most who get the opportunity to run a power-conference program like to believe they are ready for it. Most will swear that's the case as they initially are going through it. Eventually, most will admit years afterward that the change in lifestyle and responsibilities is beyond their scope of control in the early on, that they didn't really know what they were doing. It makes May's start in an 18-team Big Ten with almost an entirely new roster all the more impressive.

"I've done a poor job of journaling, just because from the day you take the job, it's a blur," he said. "I was in a Residence Inn for 90 days. I'd ask the front desk if I could change rooms a couple times just to feel like it wasn't Groundhog Day."

He'd sometimes check out of his hotel entirely and put all his belongings in his car just to feel like he had some agency over his life. Some nights he'd sleep on his office couch and pass out at 3 a.m. under an 8-foot-tall glass whiteboard affixed to the wall with any number of plays, names and other miscellany scribbled down.

May has been learning by the week about how to be better than who he was before at maybe the biggest job he'll ever have.

Izzo, meanwhile, has found unexpected joy in just how smoothly this season has gone. Surprises are guaranteed, no matter how long you're in coaching.

Another commonality between the two is their deep trust in their assistants. During MSU's film session for the Michigan game — a scout handled by Saddi Washington, a former longtime Michigan assistant — Izzo is mostly quiet. Some other assistants speak up in between Washington holding court, while the head coach sits in the back row and watches over tape he basically knows by heart at this point.

"He has a high care factor for people," Washington says. "He allows us to do our jobs. There is an expectation you be consistent, detailed and have a strong work ethic. Energy is important."

Izzo runs an ultra-disciplined, rudimentary type of offense. Get in transition, pass the ball, second-chance opportunities win games in the margins — and knock somebody on their bleeping ass fighting for a rebound. It's not hard to scout but it's hard as hell to stop when he's got a good (or better) team. This year, he's got that kind of team.

"Our staff has done a great job this year," Izzo said. "That's why we've won with maybe not as much talent as I've had in the past."

It's been six years since Sparty made the Final Four (though the 2019-20 team had a really good chance had there been a tournament). It's the longest gap of Izzo's career; his eight Final Fours only trail Krzyzewski (13), John Wooden (12), Dean Smith (11) and Roy Williams (9) for most ever. He's managed to get back into Final Four contention now, in Year 30, because he's softened on some stances without changing his worldview. Izzo is a famous sourpuss sometimes, but he's also honest and open with most to a level few coaches match.

"I think there still has to be some discipline, some accountability," Izzo said of coaching the modern player. "I think it's still going to be about work ethic. You still got to have some togetherness. I don't think those things have changed over the years."

Is it harder, to teach 18-, 19-, 20-year-olds in 2025 than it was in 1995?

"I think it's harder to keep them focused on the task at hand," Izzo said.

He recalled his teams in the '90s and early 2000s that would willingly stay late and watch games together with coaches — sometimes 15 of them in the film room — just because that's where everyone wanted to be. It's not like that anymore. Meeting ends at 7:30, see ya later. So Izzo's made a point to getting his team to Pistons games together, bringing them to his cottage, taking them bowling.

"I'm trying to keep the culture of togetherness together even more than I did before," he said. "And this group is different. What this team has done for me is it's given me faith that camaraderie, togetherness, trusting each other, believing in each other, pulling for each other. I think is here a little bit more than in some places."

As a result, this iteration of the Spartans is pacing be just the second Izzo-coached club to begin a season unranked and finish inside the top 15, joining the 2011-12 team that had All-American Draymond Green and was a No. 1 seed.

A rivalry reborn with a program rebooted

In Ann Arbor, May's day-before, pre-practice staff meeting lasts about an hour, but it barely feels like a meeting. Guys come and go, as there is an official visit happening as well (the timing is not great, but that's recruiting). May switches back and forth between asking everyone in the room their input on certain practice drills, what needs to be reinforced for MSU, watching the tape and checking his phone as texts come in by the minute.

He wants his assistants to feel ownership of everything. May is an offensive mind. He's so focused on that end, he'll allow his defense-first assistants to call everything without ever overruling their decisions.

"Not many coaches have that kind of trust in their entire staff," Boynton said.

(Having spent time around many staffs over the years, this one feels as democratic as any I've seen.)

"Daily behaviors are going to be incredibly important," May said of not just the staff, but Michigan's players. If you want to know why FAU became a nationally relevant program, it's because May recruits people who are genuinely in love with playing basketball. Guys who want to pass more than shoot. Guys who understand that sometimes it won't all be to their liking. Love of the game, love for your team, has to be what wins out.

"It's not going to go great for everyone," May said. "There's going to be guys that play better than you thought. There's going to be guys that aren't quite as good, but our temperature never changes. It's going to be the same. The daily habits, the behaviors, and those expectations and standards aren't going to change."

May's in the office no later than 7:30 a.m.. every day, usually closer to 7, and 99% of the time he beats everyone else in. He isn't a micromanager. He doesn't care when people come in, so long as the job is done. The night Michigan lost to Michigan State, the facility was empty by 12:15 a.m. with the exception of a couple of janitors and one light still on, shining into the parking lot next to the Crisler Center.

May was in his office.

He didn't wind up leaving that night until about 1:30 a.m., then was back there less than seven hours later, taking in his latest audiobooks — "Trying Not To Try" and "Thinking In Bets" — and highlighting the passages in both as he moved on to the next game prep.

"Everything we do is a bet," Mays says. "Just how the human mind works. Everything we do is a gamble."

Michigan was a gamble. But so was FAU. When he took on that depleted program, which was in disrepair, he instantly regretted saying yes after walking through the facility and initially tried to bail on the job. His wife told him to suck it up and accept his commitment. He hasn't changed his outlook since.

"Most of the guys on staff have worked with me for a number of years, and the ones that have it are, they share the same traits, where it's never going to be an emotional roller coaster," May said.

He's infatuated with absorbing as much information as he can on a daily basis, maximizing what his brain can take on in an effort to keep evolving. That's reflected in how this Michigan team plays. If you watched a majority of Wolverines games from this season and compared the offense that May is running to what he did at FAU two years ago, almost none of it is the same.

"Maybe 5%," May said.

What Michigan runs this year might largely get tossed next season. There is always something new to learn and apply. He coaches with the curiosity of a bloodhound — so that he can simplify it for his players. He equates it to an old Latin proverb: duos insequens lepore's neutrum capit.

If you chase two rabbits, you will catch neither.

"We're not trying to chase every rabbit," May said. "It's just, these are the rabbits that we need based on what we have, what we do."

Of all the analogies to use, May goes to hunting rabbits, which is fitting given his ties to Knight and the most famous story ever written about the man. The toughest rabbit of them all happens to be a different animal entirely, because Tom Izzo is no bunny. He's a beast still battling with the best of them and lording over the Big Ten.

In this his 30th season as head coach of Michigan State — his 42nd overall — Izzo's seen his league bloat from 11 members to 18. He's matched wits with 260 coaches from 163 schools in his three decades, with 60 of those coaches coming in the Big Ten. He's 732-300 overall and is the winningest coach in Big Ten history (359).

"Doesn't mean as much to me as you think, maybe someday it will," Izzo said of besting Knight's Big Ten win mark.

He's coached 153 players — way more if you count all of the Spartans he tutored for a dozen years working for Heathcote. The support staff over the years is dozens deep as well. That's a lot of people who've helped him, he'll say.

"I don't coach like I used to," Izzo said. "I'm not even in the same hemisphere as I used to, because I watched some guys try not to adjust to the times, but then I watch other guys adjust too much, and they no longer have jobs."

For Izzo, the key to thriving against your rival for a generation, let alone ascending to being one of the all-time greats, is anchored in caring more about the job and the players than yourself. As some have waited on a surprise Izzo retirement announcement, he's discovered new joy. He's not slowing down and he's not leaving anytime soon.

"If I don't want to come into work early and don't want to work late," says Izzo, and it's at this point his face turns as serious as death. "I will never cheat this place, and I will never cheat a player that I coach. Never. I mean: NEVER. That is f---ing etched in stone. So if I don't want to come back for a meeting with a player, if I don't want to give him the time, I'm going to be walking out that door that day."

You hear a man talk like this, you wonder: Who is outlasting this guy? Will this go any different for Dusty May, or will it be for him like it's been for most who came before?

College basketball has been afforded a unique reboot between two schools coached by two men with the potential to flourish beside each other near the forefront of the sport in the years ahead. One man with nothing left to prove and everyone to beat, the other with a future a bright as any coach, constantly curious to find all the new ways to end the old guard.

It's the lion in winter vs. the rabbit chaser.